By Steven E. Miller, Board of Directors, LivableStreets Alliance

Situations change and the plans we’ve made to deal with it have to change, too. But the new plans should be at least as good, at least as effective for dealing with the situation, as the originals. Which is the unsettling aspect of Boston’s current revisiting of past decisions about what to do with Sullivan Square, at the Somerville end of Charlestown’s Rutherford Avenue.

UPDATING BACKWARDS

Yes, the future opening of the Everett Casino and the Partners Headquarters in Somerville has significantly changed the situation. And, yes, it is valid to look again at what it will take to handle the potentially increased traffic. But Boston Transportation Department and MassDOT’s attempt to revive an underpass option – although slightly different than the 2013 version rejected by both the community and even Boston itself in favor of a surface design – will not allow cars to move more quickly and creates several serious new traffic flow problems. (The new underpass proposal has shorter up/down ramps but adds an additional tunnel that wasn’t in the original.) Even the traffic models developed by consultants don’t suggest that the underpass is a better option. (The traffic projection models have their own absurdity – embodying so many assumptions, pushing so far into the future, and so consistently overestimating traffic volumes, that they are hard to take seriously no matter what they show.) When compared with the surface option chosen in 2013, the underpass will significantly reduce the opportunity for economic development and open space, continue to make it dangerous to walk or bicycle across the area, and not improve access to the Orange Line station.

Even when compared to the revised surface option, developed by the city’s new consultants to accommodate the projected higher traffic volumes – which has more car lanes and lacks the previous greenway corridor – the new underpass design is inadequate. Adding insult to injury, the Sullivan Square underpass design seems tied to an effort to also revive the also previously rejected underpass further down Rutherford near Austin Street.

The new underpass proposal will not solve either the Square’s congestion or safety problems, inviting more cars into the area while not making crossing the area much better – and will continue to both injure Charlestown and violate several of Mayor Walsh’s Imagine Boston 2030 principles. It’s a lose-lose proposition. Either the underpass option has to be a lot better for both the through-drivers and the community or the city should stick with the surface-level design adopted after extensive analysis, discussion, and hard negotiations only three years ago.

CREATING NEW PROBLEMS

As shown in the excellently done, easy-to-read series of maps, drawings, and analyses on the Rutherford Corridor Improvement Coalition (RCIC) website, a major problem with the existing layout is that nine lanes of traffic (from Alford, Broadway/Maffa, and Cambridge Streets) have to squeeze into a two-lane-wide curve in front of the Teamster’s Health Center. In addition, the large traffic circle area that covers the rest of the Square is devoted to weaving lanes of car traffic, making it difficult (and nerve-racking) to drive through and positively dangerous to try to walk or bike – not to mention ugly, noisy, and useless for anything else. The pathetic reality is that the Schrafft Building finds it necessary to runs a shuttle to drive people to/from the Sullivan Square T station even though it’s only a few minutes walk away.

The proposed new version of the underpass option doesn’t significantly solve these problems. To get around the tunnel ramps and roof area it needs a crazy-X road crossing on the north side of the area adding to the complexity of several moves including accessing or leaving the T station by bus or car, and cars coming south off I-90 or wanting to turn left towards Everett – the route to the Casino entrance. (The RCIC site describes the process as “vehicles would travel on Cambridge Street, cross over Main Street extension, and then go through a sharp S curve to reach Alford Street northbound. They would then have to merge into traffic from the left - an unusual travel maneuver.”). It includes several huge intersections around the circle, including entry to the planned development on Arlington Street, completely blocking or severely impacting important walking and bicycling desire lines that would be opened by the surface option. Because of the underpass ramps and tunnel, much of the land will no longer be developable or even appropriate for green space as they would be with the surface option. (We’ve learned from the Rose Kennedy Greenway that building over a ramp is prohibitively difficult and expensive.) The cut-off sections of Charlestown on the north and west of Sullivan would remain isolated. And given the area’s susceptibility to flooding the underpass will be vulnerable.

STICKING WITH WHAT WILL WORK

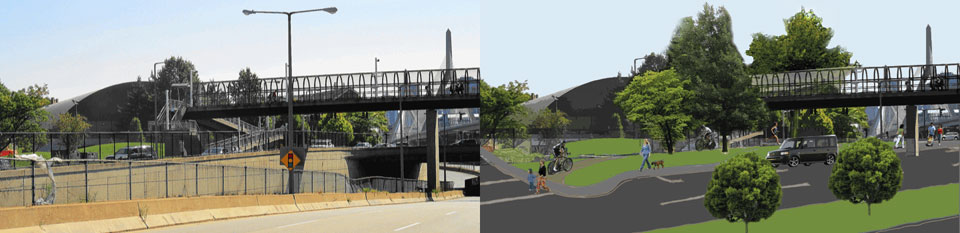

In contrast, in addition to the streets in the surface option design being narrower (and thereby slowing traffic and made easier for pedestrians to cross) than those proposed for the underpass, there are more of them. This spreads out the traffic and creates lots more space for crosswalks, bike paths, community space and parks, and developable land near the T station so that new residents in the planned developments don’t have to use their cars and add to congestion. In combination with surfacing the current Austin Street area underpass, this option will move Rutherford Avenue traffic further away from Charlestown’s resident neighborhoods. The surface option allows for pedestrian and cyclist friendly streets in both the Square and in front of Bunker Hill Community College. It will reconnect the severed parts of Charlestown now stuck behind Sullivan Station and Route 99. And it will give people a forty foot wide green corridor from City Square to the Mystic River.

As with the Melnea Cass Boulevard project on the other side of the city, the core tension behind the competing designs is between the need to accommodate both increasing regional through traffic and the neighborhood’s desire for a more livable environment. Compounding the problem is that the city’s traffic engineers and consultants continue to treat the project as a car-centered transportation issue when it really requires a multi-agency collaboration encompassing environmental, community development, and public health issues. Charlestown residents understand that cars will be moving through the streets bordering their homes. But they point out that the new plan won’t solve the congestion problem; it’s a failure even on its own terms. And even if it did magically eliminate backups, they believe that car traffic should not be allowed to so completely dominate all other considerations, in accordance with Mayor Walsh’s Imagine Boston 2030 promises.

UPDATING OR REGRESSING

There are times when updating a road plan is absolutely vital. Infrastructure projects can take a decade to nearly a quarter century to move from idea to plans to construction, with the slow arrival of funding usually the cause of delay. Engineering drawings typically sit on shelves for years, sometimes for decades. By the time the money is approved public desires and professional standards may have changed – as has happened in this past decade of incredibly rapid and widespread adoption of Complete Streets and multi-modal mobility planning. It makes sense to require every project whose design is more than a couple years old to update their plans before construction begins.

The surface option was adopted by Boston after a long and sometimes contentious community and Transportation Department process only a couple years ago. Traditional car-centric road design, coupled with fears of pushing cars into neighborhood streets, favored the retention of the existing underpasses. But local desires to reconnect the severed parts of Charlestown coupled with growing city realization about the potential development (meaning tax revenue) opportunities and backed up by additional traffic studies showing that the surface roads could handle the anticipated loads, all led to adoption of the surface option. Now, the city has backtracked and put two options back on the table – the already adopted surface option and a revised underpass (perhaps a double underpass). Charlestown advocates are worried that Boston’s Transportation engineers and MassDOT have reverted to past patterns and have already decided to use the underpass option and, if possible, to use that as leverage for reviving the Austin Street tunnel as well.

There are rumors of various levels of political pressure at play demanding continued favoritism in favor of suburban drivers. Ironically, a more regional frame of reference would actually lead to the need for transit solutions rather than road expansion because, as is no longer a new insight, the more you build the more induced demand you attract.

Upcoming public meetings will soon reveal the city’s thinking. The Walsh Administration’s transportation leaders have promised they will make the plan as good as possible, but if they are leaning towards the underpass they will have to aggressively improve the public space changes, fix the X-cross and other traffic show-stoppers, and leave the Austin Street surface option plans alone. If it’s not possible to do this – we can hope that the city has the courage to stay with the surface option.

-----------------

Thanks to Ivey St. John, Jeff Rosenblum, Charlie Denison and Liz Levin for comments on earlier drafts.

Situations change and the plans we’ve made to deal with it have to change, too. But the new plans should be at least as good, at least as effective for dealing with the situation, as the originals. Which is the unsettling aspect of Boston’s current revisiting of past decisions about what to do with Sullivan Square, at the Somerville end of Charlestown’s Rutherford Avenue.

UPDATING BACKWARDS

Yes, the future opening of the Everett Casino and the Partners Headquarters in Somerville has significantly changed the situation. And, yes, it is valid to look again at what it will take to handle the potentially increased traffic. But Boston Transportation Department and MassDOT’s attempt to revive an underpass option – although slightly different than the 2013 version rejected by both the community and even Boston itself in favor of a surface design – will not allow cars to move more quickly and creates several serious new traffic flow problems. (The new underpass proposal has shorter up/down ramps but adds an additional tunnel that wasn’t in the original.) Even the traffic models developed by consultants don’t suggest that the underpass is a better option. (The traffic projection models have their own absurdity – embodying so many assumptions, pushing so far into the future, and so consistently overestimating traffic volumes, that they are hard to take seriously no matter what they show.) When compared with the surface option chosen in 2013, the underpass will significantly reduce the opportunity for economic development and open space, continue to make it dangerous to walk or bicycle across the area, and not improve access to the Orange Line station.

Even when compared to the revised surface option, developed by the city’s new consultants to accommodate the projected higher traffic volumes – which has more car lanes and lacks the previous greenway corridor – the new underpass design is inadequate. Adding insult to injury, the Sullivan Square underpass design seems tied to an effort to also revive the also previously rejected underpass further down Rutherford near Austin Street.

The new underpass proposal will not solve either the Square’s congestion or safety problems, inviting more cars into the area while not making crossing the area much better – and will continue to both injure Charlestown and violate several of Mayor Walsh’s Imagine Boston 2030 principles. It’s a lose-lose proposition. Either the underpass option has to be a lot better for both the through-drivers and the community or the city should stick with the surface-level design adopted after extensive analysis, discussion, and hard negotiations only three years ago.

CREATING NEW PROBLEMS

As shown in the excellently done, easy-to-read series of maps, drawings, and analyses on the Rutherford Corridor Improvement Coalition (RCIC) website, a major problem with the existing layout is that nine lanes of traffic (from Alford, Broadway/Maffa, and Cambridge Streets) have to squeeze into a two-lane-wide curve in front of the Teamster’s Health Center. In addition, the large traffic circle area that covers the rest of the Square is devoted to weaving lanes of car traffic, making it difficult (and nerve-racking) to drive through and positively dangerous to try to walk or bike – not to mention ugly, noisy, and useless for anything else. The pathetic reality is that the Schrafft Building finds it necessary to runs a shuttle to drive people to/from the Sullivan Square T station even though it’s only a few minutes walk away.

The proposed new version of the underpass option doesn’t significantly solve these problems. To get around the tunnel ramps and roof area it needs a crazy-X road crossing on the north side of the area adding to the complexity of several moves including accessing or leaving the T station by bus or car, and cars coming south off I-90 or wanting to turn left towards Everett – the route to the Casino entrance. (The RCIC site describes the process as “vehicles would travel on Cambridge Street, cross over Main Street extension, and then go through a sharp S curve to reach Alford Street northbound. They would then have to merge into traffic from the left - an unusual travel maneuver.”). It includes several huge intersections around the circle, including entry to the planned development on Arlington Street, completely blocking or severely impacting important walking and bicycling desire lines that would be opened by the surface option. Because of the underpass ramps and tunnel, much of the land will no longer be developable or even appropriate for green space as they would be with the surface option. (We’ve learned from the Rose Kennedy Greenway that building over a ramp is prohibitively difficult and expensive.) The cut-off sections of Charlestown on the north and west of Sullivan would remain isolated. And given the area’s susceptibility to flooding the underpass will be vulnerable.

STICKING WITH WHAT WILL WORK

In contrast, in addition to the streets in the surface option design being narrower (and thereby slowing traffic and made easier for pedestrians to cross) than those proposed for the underpass, there are more of them. This spreads out the traffic and creates lots more space for crosswalks, bike paths, community space and parks, and developable land near the T station so that new residents in the planned developments don’t have to use their cars and add to congestion. In combination with surfacing the current Austin Street area underpass, this option will move Rutherford Avenue traffic further away from Charlestown’s resident neighborhoods. The surface option allows for pedestrian and cyclist friendly streets in both the Square and in front of Bunker Hill Community College. It will reconnect the severed parts of Charlestown now stuck behind Sullivan Station and Route 99. And it will give people a forty foot wide green corridor from City Square to the Mystic River.

As with the Melnea Cass Boulevard project on the other side of the city, the core tension behind the competing designs is between the need to accommodate both increasing regional through traffic and the neighborhood’s desire for a more livable environment. Compounding the problem is that the city’s traffic engineers and consultants continue to treat the project as a car-centered transportation issue when it really requires a multi-agency collaboration encompassing environmental, community development, and public health issues. Charlestown residents understand that cars will be moving through the streets bordering their homes. But they point out that the new plan won’t solve the congestion problem; it’s a failure even on its own terms. And even if it did magically eliminate backups, they believe that car traffic should not be allowed to so completely dominate all other considerations, in accordance with Mayor Walsh’s Imagine Boston 2030 promises.

UPDATING OR REGRESSING

There are times when updating a road plan is absolutely vital. Infrastructure projects can take a decade to nearly a quarter century to move from idea to plans to construction, with the slow arrival of funding usually the cause of delay. Engineering drawings typically sit on shelves for years, sometimes for decades. By the time the money is approved public desires and professional standards may have changed – as has happened in this past decade of incredibly rapid and widespread adoption of Complete Streets and multi-modal mobility planning. It makes sense to require every project whose design is more than a couple years old to update their plans before construction begins.

The surface option was adopted by Boston after a long and sometimes contentious community and Transportation Department process only a couple years ago. Traditional car-centric road design, coupled with fears of pushing cars into neighborhood streets, favored the retention of the existing underpasses. But local desires to reconnect the severed parts of Charlestown coupled with growing city realization about the potential development (meaning tax revenue) opportunities and backed up by additional traffic studies showing that the surface roads could handle the anticipated loads, all led to adoption of the surface option. Now, the city has backtracked and put two options back on the table – the already adopted surface option and a revised underpass (perhaps a double underpass). Charlestown advocates are worried that Boston’s Transportation engineers and MassDOT have reverted to past patterns and have already decided to use the underpass option and, if possible, to use that as leverage for reviving the Austin Street tunnel as well.

There are rumors of various levels of political pressure at play demanding continued favoritism in favor of suburban drivers. Ironically, a more regional frame of reference would actually lead to the need for transit solutions rather than road expansion because, as is no longer a new insight, the more you build the more induced demand you attract.

Upcoming public meetings will soon reveal the city’s thinking. The Walsh Administration’s transportation leaders have promised they will make the plan as good as possible, but if they are leaning towards the underpass they will have to aggressively improve the public space changes, fix the X-cross and other traffic show-stoppers, and leave the Austin Street surface option plans alone. If it’s not possible to do this – we can hope that the city has the courage to stay with the surface option.

-----------------

Thanks to Ivey St. John, Jeff Rosenblum, Charlie Denison and Liz Levin for comments on earlier drafts.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed